The Astrophonica Story

Discussion on the history and evolution of Astrophonica, the visual identity of the label and the remastering process of Clissold and The Limit.

Reissuing Clissold and The Limit shines a spotlight on the early days of my musical journey in the mid 2000s and my collaborations with Neptune. While there are other tracks of ours that could and may get reissued, the pivotal nature of these two and the ongoing demand for represses made them the perfect place to start. Reissuing them not only honours their impact on my career and Astrophonica's evolution and provides the opportunity to have them remastered on vinyl by Beau Thomas at Ten Eight Seven Mastering and on digital by Bob Macciochi at Subvert Central Mastering for a modern take in 2024. It also gives me the perfect chance to announce a brand new Fracture & Neptune release is in the works. Below is a long read on the history and evolution of Astrophonica, and the remastering process . . .

Let’s take it right back to my beginning . . . In 1995-96, I attended Islington Sixth Form College. It was at the peak of the Jungle era, just before it totally became Drum & Bass. I was already deeply obsessed and spending all my money and time on buying records from Black Market in Soho, Ibiza in Dalston, Jungle Fever in Clapton, and Lucky Spin on Holloway Road. As intense as it was, Jungle was still fairly niche in those days, and if you came across someone who was also a fan, you’d immediately have a connection and end up talking for hours.

One day at college, my friend Daniel came up and said, “There’s this guy; he’s into Jungle and reckons he can mix.” So obviously, I went straight up to him and said that I had a pair of Technics and he should come over. That guy was Nelson, aka Neptune, and we hit it off immediately, spending hours, days, and weeks mixing, raving, buying records, and making contacts. We, like many others at that time, truly lived and breathed it. It was an incredible era. In late ’99, we decided we wanted to make tracks, so started scraping cash together, managed to buy an Apple Mac G4, an E-Mu Esi4000 sampler, and started cooking. There were no YouTube tutorials or resources like there are today, so we just had to make it up as we went along, going off folklore and rumours of how to achieve a certain sound. As a result, our first few tracks were quite experimental and didn’t fit the straighter, noisier style of Drum & Bass that was emerging, but we doubled down and started carving our own psychedelic sound with influences from early Jungle, Danny Breaks, Paradox, The Steve Miller Band, and Hip Hop’s sample-heavy aesthetic.

Around the same time, we both got shows on North London’s Rude FM 88.2, cut some dubs of our crude early attempts at the legendary Music House, and became part of the emerging Inperspective Records night, Technicality, at Herbal with a load of other like-minded misfits. Playing there really helped us hone the sound we were after and gave us the confidence to send our music out. So we put together five tracks, burned a few CDs, and posted them out to a handful of people we respected. To our total surprise and disbelief, Danny Breaks replied, saying he wanted to release two of the tracks—Discharge and Deadlands—and those became our first release in 2002 on Droppin’ Science. We upgraded the studio a bit with an E-Mu 6400 Ultra, a Mackie desk, and some outboard processors to refine the sound.

Music on Inperspective Records, Paradox’s Outsider, and Dublin’s Bassbin followed over the next few years, but in 2008 Clissold was the first track that started to get play outside of our well-loved but niche circles. Support came from dBridge, Doc Scott, and DJ Flight, who consequently signed it to her new label, Play:Musik, which we were incredibly excited about as we had been fans since her Rinse FM shows at the end of the 90s. Unfortunately, due to problems at the distributor, Play:Musik was put on hold, leaving Clissold at the mercy of the dubplate dungeon. We knew this track had potential and really didn’t want it to fade away, so we decided to release it ourselves in 2009 and thus, Astrophonica.

“Clissold” is the name of a park in Stoke Newington, North London, situated roughly halfway between where Nelson and I grew up. I learned to swing in the playground there. It’s also where I first heard Acen’s Close Your Eyes playing from an older friend’s cassette player. After meeting Nelson, we played weekly football matches in the park. We both decided that the airy guitar sample reminded us of sitting under a tree in a park, so “Clissold” felt like such a perfectly unique fit. Memories of making this one are hazy, but it was created using a mix of Logic Audio on the drums and samples and, of course, the E-Mu sampler on the bass. I do remember Nelson going sick on the MIDI keyboard whammy bar, controlling the filter cutoff on the bass and then repeating the process on the Mackie 1604-VLZ Pro EQ to accentuate the movements. You can hear it when the bass starts to open up and move around as the track progresses. We worked like that a lot together, trying to make each other laugh or get excited with live EQ sweeps or reverb sends.

In 2010, we released The Limit, and this one really put the label on the map. I remember hearing it a lot at Sun And Bass that year. It started with a break I got from Zero T, who lived over the road at the time. I spent about two weeks on it, EQing, compressing, and resampling. Somehow, I didn’t get bored of it, and during one session, we started jamming over it with a reese bass from the E-Mu, but nothing quite stuck. I have a clear memory of Nelson taking a phone call while I carried on noodling about with the pitch bend on the reese. He suddenly looked over mid-conversation with the bass face and mouthed, “Yeah, that’s the one!” Moments like this are what make collaborating so special. To me, I was just messing about, but Nelson, who had zoomed out a bit to take the call, heard the potential, so we went with it. Working alone can lead to getting stuck in an endless loop of possibilities or even missing the ‘gold’ by getting too zoomed in on the process and the detail.

As time went on, I began working more as a solo artist and decided to expand the label to include music beyond just my own. I always strive to create and promote music with lasting appeal, music that has that special "x factor," both as an artist and when I'm doing A&R for Astrophonica. In both roles, I'm constantly seeking out interesting, character-filled music with a unique aesthetic. From Dawn Day Night to Sully to Nikki Nair to Damian’s Ghost, I look for tracks that will continue to evoke strong reactions far into the future. It’s now a place for myself and other artists to try things and ‘double down’ in the same way Nelson and I did right back at the beginning.

It’s important to discuss the visual identity of Astrophonica as it, too, is an integral part of the story. At the same time as we started the label, my brother Harry and friend Nick were in the early stages of their careers as the design studio ‘UTILE’. Harry comes from an illustration background, while Nick specialises in digital design, and between them, they were able to come up with a hand-drawn, textured aesthetic presented in a modern digital world—perfect for Astrophonica. Initial reference points were Danny Breaks’ Droppin’ Science, the jazz label CTI, and the practice of astronomy. They took that and ran with it, taking those references and transforming them into something entirely unique and identifiable.

From the detailed and distressed center labels for the first releases to the clean and striking interlocking hand image for Nikki Nair’s Renormalization Support Group, UTILE have been in control for the entire journey. The look and feel of the label’s art is all their own direction, and they nail it every time. It’s an extreme privilege to be able to give someone autonomy on design and have total confidence in how each release will be represented visually. The hand-drawn approach has always been at the center of Astrophonica’s visual style, and along the way, we’ve incorporated many different processes. The sleeves for 2011’s Customtone, which Harry and I printed individually using a lithographic plate and press in our kitchen in Harringey, involved quite an industrial process. It took two whole days of carefully applying enough pressure on the press so the ink would stick, but not so much that it would squash the seam of the sleeve. The painstakingly hand-drawn, digitally animated video to accompany Customtone is nothing short of breathtaking and is a perfect example of the two disciplines blended in their work. There’s so much more I could write about their work and contribution to the label that it deserves a dedicated piece, which I will put together in the coming weeks.

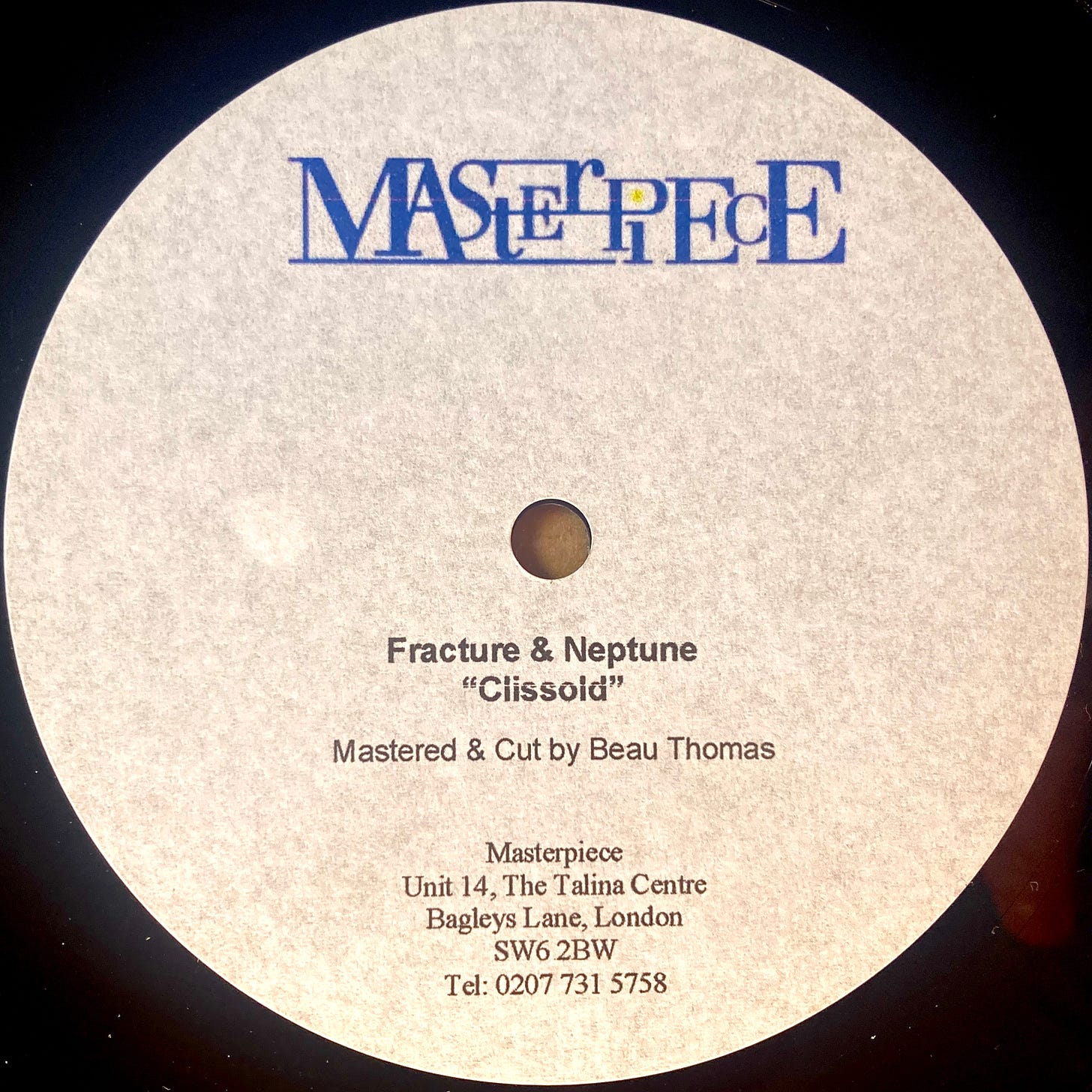

The original stampers for both Clissold and The Limit are long gone, so new ones were in order for this reissue. Beau Thomas at Ten Eight Seven Mastering (fka Masterpiece) did the first ones, so it was a no-brainer that he should do the recuts too. The originals were quite aggressive, with some of the top end on the edge of breaking up, which I absolutely love. That sound always reminds me of old DJ SS tunes cut at JTS—the hats on the edge of becoming white noise.

The purpose of vinyl has changed over the years and is, for me at least, now more of a home listening format. I thought it would be nice to reflect that in the recuts, so we went for a more open and smoother aesthetic, which I’m incredibly happy with. Beau was such a huge help at the beginning of Astrophonica. The first few sessions were attended cuts, which meant Beau could give us direct feedback on our mixes and demonstrate issues when cutting to vinyl, which is a picky little so-and-so of a format. There are some things it just doesn’t get on with at the levels we were pushing our cuts to—like shakers, tambourines, and cymbals. This was invaluable knowledge and certainly had a positive effect on the sonic side of my music.

We also took the decision to remaster the digital versions, not because we didn’t like the old ones, but because it gave us a chance to hear a new take on them by Bob Macc at Subvert Central Mastering. Mastering tools have come a long way since the original versions came out, so new approaches are now possible. People have long wanted their music to sound loud, louder, and even louder, and previously, that often just meant clipping or limiting until it still sounded okay. With developments in software and new solutions to the ‘loud but clean’ problem, engineers are now able to go louder with refined control, thus retaining clarity. There have also been huge leaps in EQ technology in terms of what parts of a full track you’re able to EQ. Honestly, this isn’t the place to get technical about all of that, and I’m not the right person to do so, but Bob told me, “You can work with the underlying structure of the track so you can cut stuff without killing all the drums, which allowed me to work with Clissold in a little bit more detail.” I think you can hear both of those improvements in the remasters. They’re louder, cleaner, and have more detail in the drums. I will always hesitate to use the word ‘better’ when talking about loudness and clarity because it simply isn’t the case, but I am extremely pleased with how these turned out, and they’re definitely closer to how I would mix them today.

I’ve known Bob since the early 2000s. He was a part of the Technicality and wider experimental breakbeat Drum & Bass scene too. He released tracks on Paradox’s Outsider around the same time we did, and we all shared a mutual, cult-like appreciation for each other’s music. He was already ahead of the pack in terms of understanding mixing and mastering and, over the next few years, built an empire. In 2011, Astrophonica released Retrospect: A Decade of Fracture & Neptune. This compilation covered the first 10 years of our music and included tracks from various labels, including our debut release on Droppin’ Science. At the beginning of the millennium, releasing underground music digitally wasn’t common; the market was entirely vinyl. We’re incredibly proud of this work and wanted it to be accessible to everyone in full quality, rather than just as vinyl rips on YouTube. The remastering of Retrospect needed to be done with care and a love for the music, so Bob was the guy.

Nelson and I went to see him at his secluded home mastering studio and spent the weekend totally geeking out about the whole process. He did an incredible job, particularly on some of our older releases like Colemanism and Too Doggone Funky, which, at the time of making, I had no idea what I was doing (it’s quite possible I still don’t). The mixes were made on rudimentary equipment in a totally untreated bedroom. It was quite a moment hearing Bob in real time make them sound like I had wanted them to sound in the first place. Since then, Bob and I have had many conversations about mastering and how he can help me achieve the sound I want in my music. Relationships across any large-scale and ongoing creative endeavour are essential, and I’m lucky to have an engineer with whom I can truly be honest about their work and also trust completely with their critique and judgement on my work. Mastering, and particularly my relationship with Bob, is another topic that deserves a piece of its own.

It's incredible that 15 years later, people still want these tunes. Both played a pivotal part in my career and the evolution of the label and it is an absolute pleasure to present the Clissold and The Limit 2024 remasters.

Lush read, thanks for sharing