March 2025 sees the release of Flobama’s debut Astrophonica EP Orion Sound and accompanying sample pack produced entirely on the Amigo Sampler, an emulation of the legendary 1980’s Commodore Amiga. The following is a long read on Flobama’s unique sound, the Amiga’s continued impact on UK Jungle music, the development of the Amigo Sampler and the concept of limitation in creativity…

EP available on 12” & digital now

I admit it—I was doom scrolling on the ‘Gram. But this time was different. Between the memes and cats, a grainy, oversaturated, lo-fi video stopped me in my tracks. A bulky grey Orion CRT TV & DVD combo displayed the recently developed Amigo software, with the text overlay: "Making Old Skool Jungle With Amigo Sampler," alongside some of the sickest, most unique, crusty Jungle I’d heard in a while.

The visual and conceptual aesthetic grabbed me, but the music hit even harder—raw, undiluted, psychedelic Jungle with shades of classic Hip-Hop, cosmic UK rave pilot Danny Breaks, and the celestial fusion that underpins Astrophonica.

As a longtime admirer of Jungle pioneers like Bizzy B, Equinox, Aphrodite, and Paradox—who built their sound on the 1980s Commodore Amiga—I too had been experimenting with Amigo, an incredible new sampler by fellow Lo-Fi Jungle enthusiasts PotenzaDSP and Stekker which emulates and captures the magic of the original Amiga’s crunchy sound, so I felt an immediate connection and was intrigued to find out more about Flobama’s work.

We began talking, and it turns out he’s a big fan of Machinedrum’s 2013 Astrophonica appearance Clissold VIP and had loads more 100% Amigo-produced Jungle demos. As is often the way with Astrophonica, the stars aligned, and it was clear Flo should become part of the fam. The track in the video, WYGnD, became the first on this new EP and we began collaborating and curating the rest immediately.

We’ll get into the recently developed Amigo Sampler in a bit, but first let’s understand the significance and influence of the original 1980s lo-fi badbwoy that helped define early Hardcore and Jungle’s identity. I am certainly no Amiga Jungle historian, nor have I ever used one to make music, but I have great appreciation for the underground UK artists who did and the incredible music they made with it. So here we go . . .

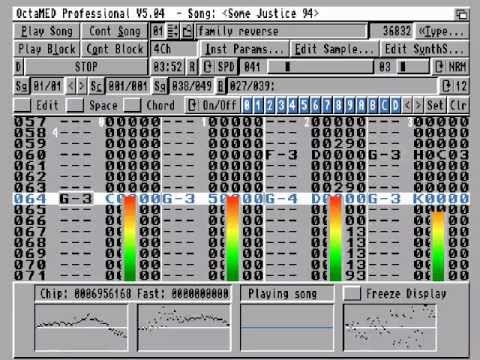

In the 1980s, Commodore released a range of affordable home computers called Amiga. As a kid, I knew them for their gaming capabilities and vast range of iconic titles and spent hours zapping enemies on Xenon II. However, with the OctaMED sequencing software and the Amiga’s Paula audio chip—which allowed for onboard sampling and limited 4-channel audio playback—it was also now possible to make music on a budget from the comfort of your home.

Of course, this affordability came with compromises. The Amiga had a maximum bit depth of 8-bit and a sampling rate of 23kHz—far below the professional equipment of the 1990s, when 16-bit/44.1kHz samplers matching CD quality became the industry standard. These limitations resulted in a loss of frequencies, particularly in the higher range, along with a lack of depth and definition in the sound. Think of it as the audio equivalent of a pixelated early digital photo or classic video game graphics—blurry, blocky, and missing fine details, yet still recognisable and full of character. Along with this clumsy and jagged digital representation comes a new aesthetic and, dare I say it, beauty. Artifacts are introduced, and once-simple, clean tones become sizzling harmonic textures, while thin, delicate drums transform into punchy, dense mammoths that hit harder than a button-mashing boss fight. This unintended side effect gave Amiga-produced music a raw, gritty, and undeniably powerful sound.

Despite Andy Warhol and Debbie Harry being part of the world premiere of the Amiga 500, the affordable home computer never penetrated the studios of underground producers in the U.S. as it did in the UK. While the U.S. is known for equally important lo-fi beat machines like Akai’s MPC range and the E-Mu SP1200—pushed to the limits by greats like Dilla, Pete Rock, and Madlib—the original Amiga alumni were dominated by a crew of UK junglists such as Bizzy B, Equinox, Urban Shakedown, Dlux, TDK, Zinc, and Paradox. It’s suggested that megastars like Aphex Twin, Calvin Harris, Mike Oldfield, and Kanye West have used Amigas running various pieces of tracker software, but that distinctive sound will forever be linked with raw, DIY bedroom Jungle.

As wonderfully warped and iconic as the sonic quality became, at the time it wasn’t so much an aesthetic choice as Marlon Sterling, aka Equinox, puts it in a Guardian article: “It wasn’t the sound I used the Amiga for, it was all I could afford. Back then, you needed all sorts of hardware to make music, but just having the Amiga sound sampler and OctaMED, you could get great ideas down without the need to hire a studio. It was the poor man’s studio – even the software was free!”

The brutal effects of the Amiga are on full display in Equinox’s Acid Rain, originally written in 1996, pushing the poor Paula chip to the absolute limit of its sonic capabilities and bass thresholds. It feels like the Amiga is on the verge of imploding under the sheer weight of its own sonic mayhem.

Bizzy B’s 1993 darkside jungle hellscape Twisted Mentasm also bears the hallmarks of the classic Amiga lo-fi fizz, look out for the hissy digital by-products in the chaotic pitch-bent rave stab–a dystopian bitmapped fever dream.

Perhaps the most famous of the countless Amiga-produced jungle and hardcore tracks is Urban Shakedown’s 1992 hardcore classic Some Justice—a euphoric confluence of dub, hip-hop, and breakbeats that became a rave anthem, uniting us all in ecstasy “as one family.” The UK chart hit was apparently made using two Amigas synced together for extra sample time and tracks—though in reality, it was just a case of pressing play on both machines simultaneously. You can hear the signature Amiga crunch on the first flanged FX hit that opens the piece. Also, note the aliasing on the bass sweeps, creating that distinctive top-end buzz.

Urban Shakedown member Aphrodite’s back catalogue is packed with Amiga-produced masterpieces. Beat Booyaa showcases his signature explosive and energy-filled drum science, featuring tight rolls and pitched snares bursting with euphoria and low-resolution charm.

There are so many more, and I could easily go on for days, but a few personal Amiga standouts include Formula 7’s It’s Not Just Ragga, Foul Play’s Dubbing You, and DJ Red Alert & Mike Slammer’s In Effect. To my knowledge, all of the Slammin’ Vinyl releases were 100% Amiga produced. I love them all, but In Effect stands out. The crunch is present throughout the record but is particularly evident on the piano stab and the entire mix teeters on the verge of falling apart, only adding to its intensity like an overwhelming ecstasy experience. Section after section of pure bliss, waves of rushes, and all the peaks and dips of a ’90s rave experience.

Paradox has been producing music on the Amiga and OctaMED since 1992, starting with DJ Trax as Mixrace. He still uses it—not out of nostalgia, but for its unique sequencing and pattern editing capabilities, which he uses to trigger external samplers for a cleaner sound. Unlike modern DAWs with MIDI piano rolls, OctaMED relies on hexadecimal coding, which he insists enables the tighter, more precise, and focused breakbeat editing that became the defining character of his sound.

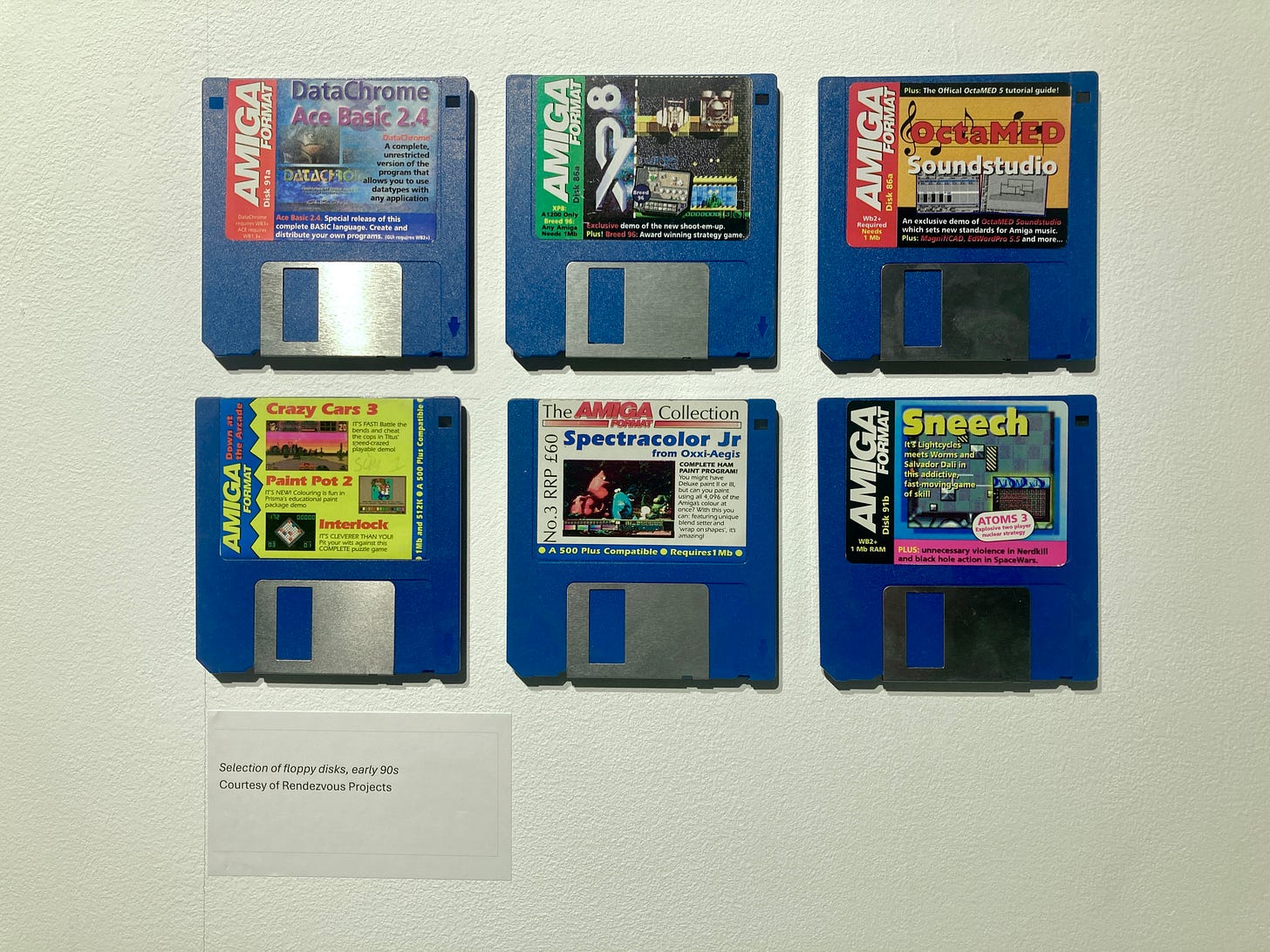

The Commodore Amiga’s sound and aesthetic are enjoying a reboot as people rediscover the magic in limited tools after years of chasing pristine, high-resolution audio. In 2024, Rendezvous Projects held Trackers and Breakbeats, a London exhibition exploring the groundbreaking influence of Bizzy B’s Brain Records and its pioneering use of 8-bit tech in the ’90s. Despite its niche subject, the event drew a diverse crowd—Old Heads and Gen Z alike—a testament to the Amiga’s lasting impact.

The exhibition featured photography, flyers, and oral history, but the standout was a live Amiga demonstration by Bizzy B and Equinox. Watching these two Amiga veterans fly through key commands and inputting code to chop drum breaks on the fly was mesmerizing—a true performance, not for the audience, but on the Amiga itself, much like a guitarist playing their instrument.

During the performance, Bizzy B stopped to say, “The beautiful thing, and what all the fuss is about, is this computer has a sound chip that was unbelievably advanced for its time. Now, the sound quality was really low, and at the time we were always fussing over quality, but what we didn't realise is that this sound quality gave our music a totally unique sound from the other contemporary £30,000 studios.” Bizzy B really is an Amiga legend and his YouTube channel is full of tutorials, history and demonstration. Well worth checking out for some deeper, first hand knowledge and discussion.

2024 also saw the release of the Amigo Sampler, which began as an idea from modern jungle producer Stekker. Teaming up with computer science student and plugin developer Dario Potenza, their mission was to recapture the iconic sound and focused intent of the Amiga. Over email, Stekker told me that while he’s drawn to the Amiga’s “zen-like workflow with no internet or distractions,” using one in the modern age comes with many obstacles—sometimes, he just wants to “be on the couch with a laptop and quickly make something.” Dario adds that the philosophy behind Amigo is “simplicity and affordability, while balancing old-school charm and new-school convenience. So we tried to keep it to the most core, essential, musical toolbox a jungle sampler needs.” Their deep respect for the Amiga’s defining workflow and sound is clear, and this new emulation further cements its place in jungle music history and continues the legacy. They’ve done a great job and I’ve been using Amigo a lot in my recent productions–it’s full of the imperfections and degradation you need for a classic sound. It’s important to note that tools don’t make good music by themselves, and just because you use some old piece of kit doesn’t mean you’re automatically going to have an authentic sound. However, there’s something about the limitations of Amigo—both sonically and workflow-wise—that seems to encourage having fun and disregarding the ever-present obsession with loud, in-your-face mixes.

Pete Cannon, the relentless Barrow-in-Furness rave machine currently living in North London, is one of many modern-day producers working with vintage tech. He’s incredibly passionate and infectious when it comes to creating new hardcore and jungle tracks using authentic gear. He grew up using the Amiga and OctaMED, so he has a deep affinity for it. Clearly nostalgia plays a big part in anything vintage or retro, but is there something else?

On my 0860 podcast, I asked Pete how the limitations of old and often basic technology affected the process, “you’re pushed to learn and you’re pushed to pull the trigger quicker, when you make a decision quicker you get to the point quicker, you get into a flow. When you get into a flow you start making the full tune.” This is something I totally agree with and it’s potentially a more important ingredient in classic music than the sound of gear used.

I love using modern software with its endless capabilities and vast hardware storage space, but that is almost its downfall. It’s all too easy to get stuck in the endless possibilities, searching for the perfect sound and adding too many elements until you lose track of your original idea. I find that when I get stuck in the mindset of having to add something to make a track come to life, it usually means the core idea isn’t strong enough.

On the Amiga and with other limited music-making processes, there is literally no space for noodling. Sample time was at a premium, meaning you had to think carefully and be more decisive with the samples you chose, rather than relying on the gigabytes of kick drums we now have available to throw in at any time. Programming time was also a costly resource—it could take you all morning to chop and program a few bars of drums, so you had to make sure your idea was strong, get it right, and commit to ‘tape’, as they say.

OctaMED didn’t have an undo function. Just imagine that for a minute in this age of multiple and selective undo history. If you made a mistake, you had to manually undo it by recreating what was there before. I doubt this is a feature that the pioneers miss but in practice I can only imagine that it must make for a more committed and focussed approach to the workflow.

With only four channels of audio, limited sample time, and low resolution, how will your idea come across? Is it strong enough, or does it need simplifying and refining down to its core? It can be all too easy to hide behind the capabilities of modern gear, but when working within strict limitations, you’re forced to focus on the essence of your idea.

8-bit video game graphics needed to be engrossing at the concept stage, and that idea had to remain coherent even in low resolution. Think about how iconic the early Nintendo characters were, and then consider how few pixels were actually used to depict Mario. He really is just a few blobs, yet you recognise him immediately. Many of the most enduring ideas are simple, surviving even when stripped down. There’s something powerful in that

.

Let’s end up where we started with Flobama and the new Orion Sound EP. How does he fit into all this? To my ears, Flobama manages to blend elements of UK Jungle reminiscent of the frantic, twisted breakbeats of Bizzy B, the extreme, brutal bass of Dillinja and the astral vibes of Danny Breaks with laid-back-loud-pack elements from US Hip-Hop beatmakers J Dilla, Pete Rock, and Madlib who channel the Jazz greats before them through dusty vinyl samples and neck snapping grooves.

The Orion Sound EP effortlessly fuses all of these things without ever sounding like any one of them specifically. The music is raw and loose—not in a lazy way, but in a way that values ideas and funk over pristine engineering and (over)processing. Limitation evidently plays a big part in his production process and his music is full of character and that unique quality I always look for in artists for Astrophonica. His music sounds like… Flobama. I feel like even after a relatively short time of hearing his music I could spot one of his tracks in seconds which is a crucial attribute in a time where a supposed 120,000 new songs are uploaded to streaming services each day.

Love the samples used in Flo’s record. Snaking through a lot of atmospheric favourites from back in the day like Seba’s - Connected etc.

Fantastic read! So rich, Will be coming back to it.